Value Investor INSIGHT

Value Investor INSIGHT

Jiro Yasu of VARECS Partners describes why capital allocation at Japanese companies is often abysmal, the extent to which that’s changing, key lessons learned from First Eagle Investment’s Jean-Marie Eveillard, why he has the perfect name for a value investor, and what he thinks the market is missing in Medikit, EM Systems and CRE Inc.

After 10 years working in New York, much of that at First Eagle Investment Management, Jiro Yasu returned home to Tokyo in 2005 to take over his family’s brokerage business. Pivoting from that long-held plan, however, he decided the family should sell the brokerage and that he would instead start a value-investing firm, co-founding VARECS Partners in 2006.

Targeting small companies that have good or improving capital-allocation skills, VARECS’ VPL-I Trust since Yasu became its sole portfolio manager at yearend 2009 has earned a net annualized 14.0%, vs. 9.6% for the TOPIX index. He’s finding opportunity today in such areas as medical devices, medical software and real estate.

Value investors in Japan are a fairly rare breed. How did you find it or it find you?

Jiro Yasu: Stock investing has always been around me. My family ran a brokerage business that was originally founded by my great-grandfather, and in high school my father told me I would be his successor and asked me to study economics and get some relevant experience outside of our company to prepare for when he was ready for me to take over. After graduating from college in 1996 I moved to New York and worked for two years at Daiwa Securities before getting a job at Arnhold and S. Bleichroeder, which during my time there became First Eagle Investment Management. I worked first in marketing and then on selecting managers for a multi-manager portfolio at the firm, but over time I got to know both Jean-Marie Eveillard and Charles de Vaulx, who recommended a number of things for me to read about value investing and who from time to time would let me help out with research when they were looking at Japanese companies.

After my father asked me to move back to Japan in 2005, fairly soon I concluded that we should sell the brokerage business and that I was more interested in starting my own firm to pursue value investing, which as you say, is not that typical in Japan. We did get out of the brokerage business and I and two partners started VARECS Partners in 2006 with money from my family, from the Arnhold family of First Eagle, and from one institutional investor.

The Chinese character for my last name has the joint meaning of cheapness and safety – perfect for value investing.

Describe your original strategy and how it has, or hasn’t, evolved.

JY: What we look for hasn’t changed. We try to find small, overlooked companies – usually less than $500 million in market cap – earning 10%-plus operating margins through strong market positions in businesses that are relatively stable and that have some industry tailwinds. We’re not expecting super-fast growth, but we want there to be a high probability that the business will expand over the next five years and that through operating leverage profits will grow even faster.

We want some kind of downside protection in the form of tangible assets like cash or valuable real estate – something to protect us if we’re wrong about the value of the operating business. Finally, we are very price sensitive. Some value investors will say today that anything less than 10x earnings before interest and taxes on an enterprise-value basis is cheap. For us cheap means 2-3x EV/EBIT – maybe 6x for the very best businesses.

What we try to avoid also hasn’t changed: businesses with low barriers to entry, frequent technology disruptions, short product cycles, little pricing power and long payback periods. High leverage is a red flag – good businesses should have strong balance sheets – as is aggressive behavior related to accounting, deal making or balance-sheet growth.

Initially we may have put more emphasis on being hands-on with the management of companies we own. We very often have opinions on the best ways to realize shareholder value and we are not at all shy about communicating them, but we’re also more than happy to generate returns by doing nothing on that front. Now any activist-type suggestions we make tend to be just an added bonus rather than central to our thesis.

Please give an example or two of the type of business you favor.

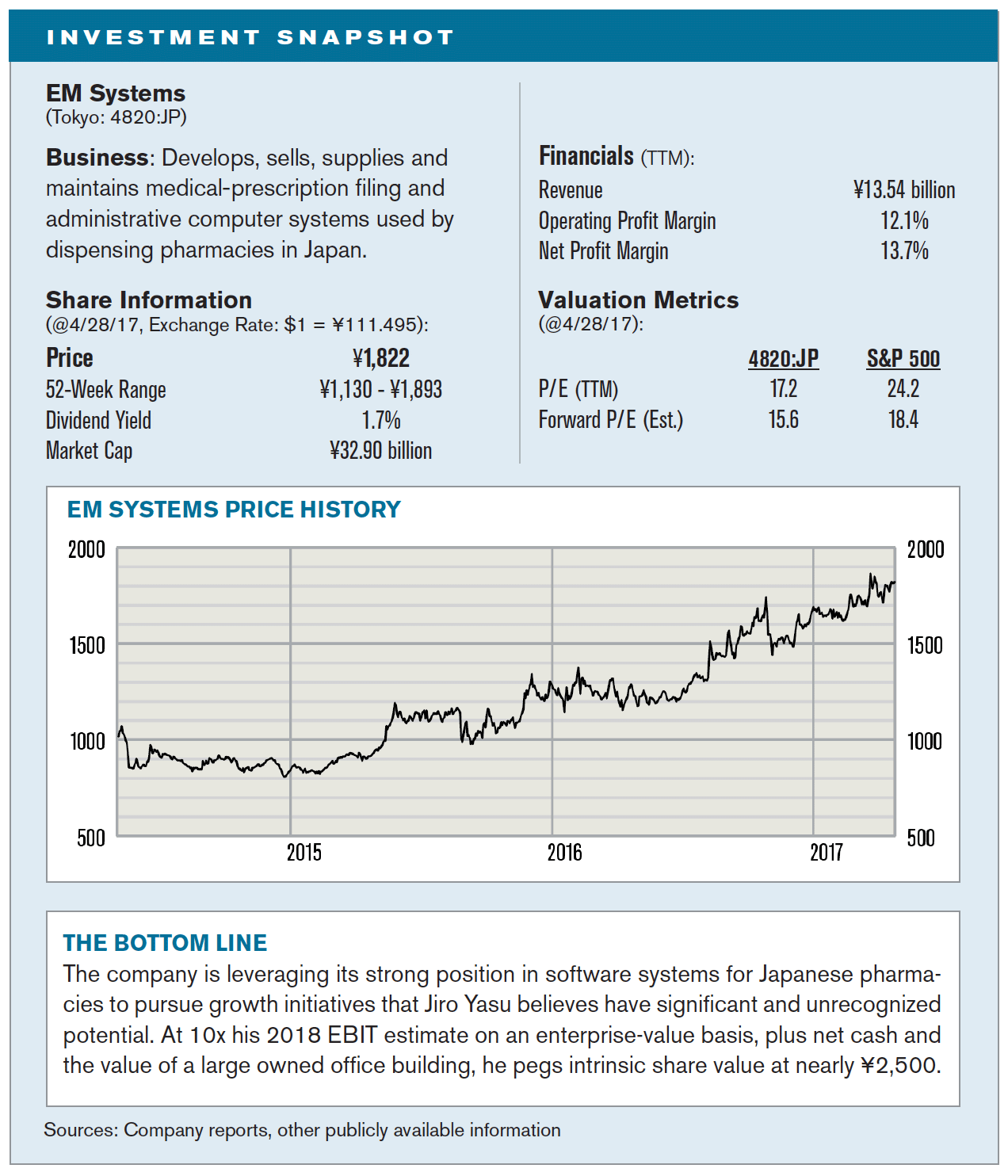

JY: One of our largest holdings is a company called EM Systems [4820:JP], which sells software used by pharmacies in Japan to manage their businesses. It’s the #1 player, with about 30% of the market. It has shifted more to a subscription model, with highly recurring revenues. Customer switching costs are high, and incremental growth is driven by an aging population and the potential to buy smaller competitors as the industry consolidates. This type of business profile is attractive to us.

Another example would be Asante Inc. [6073:JP], which offers termite-control services. This isn’t exactly a sexy business, but the climate in Japan is conducive to these types of bugs and you have to treat your house on a recurring basis to keep them away. The company also has potential tailwinds from higher marketpenetration rates, expansion in western Japan from its traditional base in the east, and from government regulations to make houses usable for a longer period of time. As it continues to grow, that should reinforce its market leadership.

How do you surface ideas?

JY: We don’t do much screening. I take some of that from Jean-Marie and Charles at First Eagle, who thought that valuation screening based on published numbers – which they were always skeptical of and looking to adjust – wasn’t that helpful.

One thing we do is monitor carefully M&A transactions done around the world and then try to see if there’s something related in Japan that is worth a look. As Disney was buying up Marvel and Pixar and Lucasfilm, we started looking at Japanese animation companies. When Berkshire Hathaway bought Iscar, we starting learning about the cutting-tools business.

More recently we’ve read a lot about how the music business after years of decline is finally turning around as paid services like Spotify and Apple Music gain traction. Connecting some dots, we earlier this year invested in Amuse [4301:JP], a talent-management company for Japanese artists, musicians and actors that also organizes large-scale live entertainment events. After less-than-positive earnings news, the shares had fallen 30% over the previous year and when we bought in the enterprise value after taking out cash was around $100 million. In a good year the company can make $40-50 million, so on that basis we thought it was very cheap.

One other thing I’d mention about our process is that we’re known as a firm that will take almost any Investor Relations meeting we’re offered. For some companies that are too small or too boring, brokers sometimes have a hard time lining up institutional investors to meet with management. We’ll take the meeting. There’s always something to learn and maybe we’ll get an investment out of it.

You wrote a paper not long ago in which you discussed some root causes of the often-abysmal capital-allocation practices at Japanese companies. Can you share the CliffNotes version here?

JY: The most common reason for the undervaluation of Japanese companies is poor capital allocation. What I wrote about was the concept of longevity and how it is generally revered in Japan. The current Japanese emperor is the 125th, representing a continuing succession for over 2,700 years. Ise Jingu, the most important Shinto shrine in Japan, has been rebuilding its facilities every 20 years for over 1,300 years. I found a statistic that there were 5,586 companies in the world that have over 200 years of operating history, and 56% of them were in Japan.

When we talk with CEOs of cash-rich Japanese companies and ask them why they hold so much cash, the reason is almost always to make sure their company survives no matter what might happen in the world. We looked at one mail-order company in Kobe, Felissimo [3396:JP], that had a market capitalization of about $90 million and net cash of $130 million. It was ironic that even though the enterprise value was negative, the EV/EBIT multiple was positive because the company regularly lost money. Management argued that keeping all the cash was essential to the company’s future, but it was obvious to us that it was just a crutch that allowed them to postpone needed cost-cutting.

Another interesting example is Japan Digital Laboratory, which we looked at before it was acquired late last year. It had a tax-accounting software business that earned over 25% operating margins, but the return on equity for the entire company was maybe 5%. That’s because it held over $500 million in net cash and for some reason operated a commercial airline with low-single-digit operating margins.

These may be extreme examples, but we see similar problems with many Japanese companies: too much cash, large cross shareholdings and poorly performing non-core businesses, all of which dampen returns on equity and stock valuations. As much as you want to believe that poor capital allocation can’t go on forever, you can’t succeed in investing in Japan without partnering with management teams that understand the difference between prudent management of capital and destroying value.

What to you constitutes a bargain?

JY: I am of the Jean-Marie Eveillard school, focused on EV-to-EBIT. One of my early partners was a buyout guy who tended to focus more on EV-to-EBITDA, and while I originally didn’t think there would be a big difference, we found out in 2008 that the stocks that looked cheap on EV-to-EBITDA went down a lot, while those that were cheap on EV-to-EBIT held up much better.

I try to estimate the normalized annual EBIT level a company can sustain and then apply to that the multiple a rational buyer would pay for the whole company. For the target multiple we look at similar businesses overseas as well as prices paid in past deals, but we don’t just blindly apply multiples from elsewhere to Japanese small caps. Termite-control companies like Asante are highly valued in the U.S., for example, at 16-18x EBIT. But for our fair values we generally assume 6x, up to maybe 10x for the very best businesses.

From there, we keep it very simple. If we believe EBIT will normalize at $100 million and the multiple should be 8x, we think the business is worth $800 million. If the company has $200 million in net cash, we arrive at an intrinsic value for the company of $1 billion. We then want to be able to buy the stock at least at a 30% discount from that intrinsic value.

How concentrated is your portfolio?

JY: We typically have 20 to 30 holdings. If we have very high conviction, we will have positions that are as much as 10% of the portfolio, which is roughly the case today with EM Systems, Medikit [7749:JP], CRE Inc. [3458:JP] and Agro-Kanesho [4955:JP]. Part of our conviction in companies like this is that we have good relationships with the management teams and believe their interests are completely aligned with ours. Beyond the biggest positions, we have a number of positions of around 2% of the portfolio. These could be core positions one day or were core positions before, or for some other reason we are just more comfortable holding a smaller position.

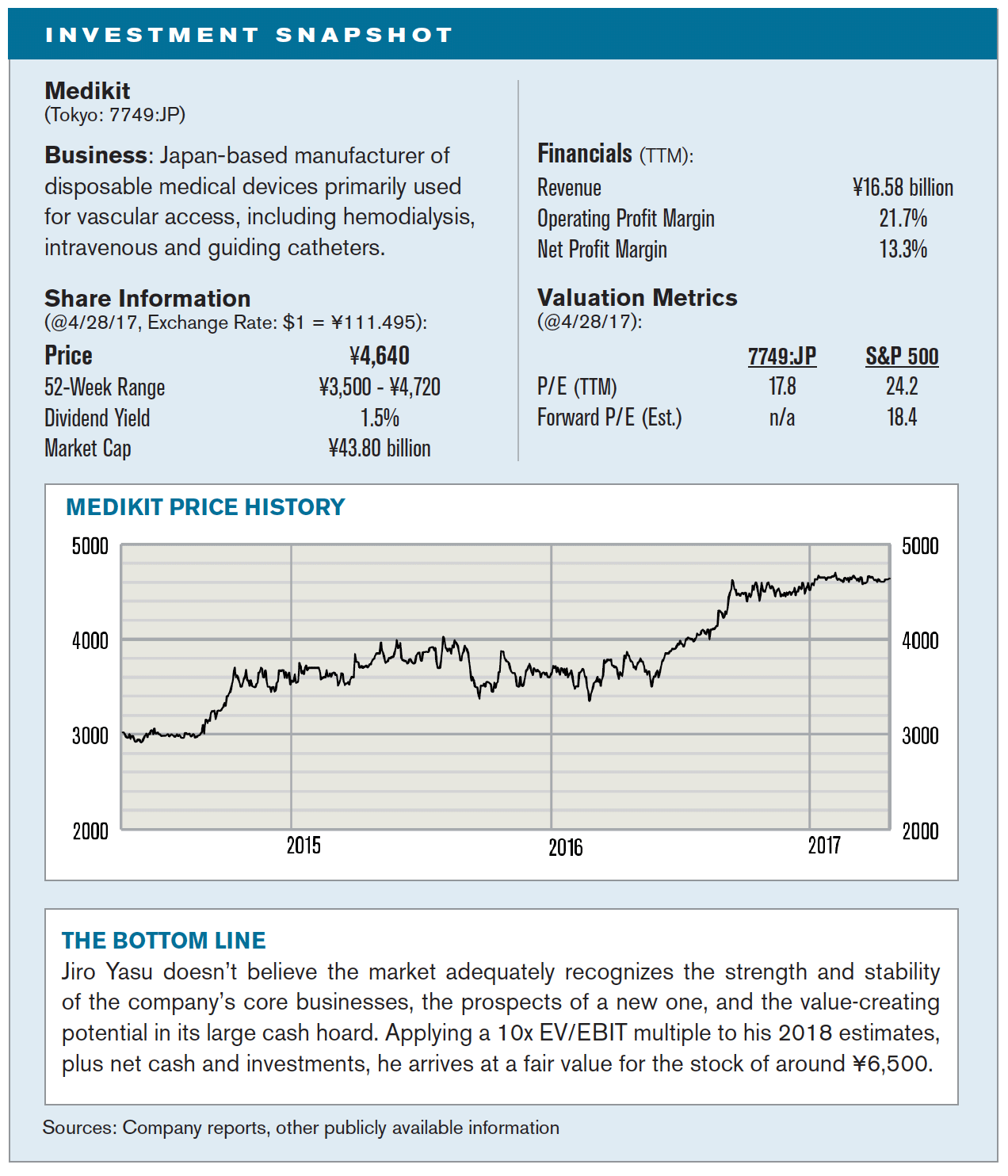

Let’s talk in more detail about some of your large positions. What do you like about medical-device maker Medikit?

JY: The company has over 50% market share in Japan for two core products: catheters for kidney-dialysis treatment and intravenous catheters with a special valve that prevents the reverse flow of blood upon insertion. Currently 90% of revenue comes from Japan, with one-third of that from dialysis catheters. That’s a great recurring business, as there are 300,000 kidney-disease patients in Japan who need on average four dialysis treatments a week, for which they use two catheters each time. The number of such patients should continue to increase as the population ages and as changes in diet have increased the incidence of diabetes in Japan.

We first invested in the company in 2008 when despite it having 20% operating margins and a strong dialysis franchise, its stock traded at a negative enterprise value – net cash exceeded the market cap. It was then just launching its new IV catheter, which we considered a real innovation, and it steadily took market share to now be the dominant product on the market, generating roughly one-third of total company revenue.

Is there anything new on the horizon, product-wise?

JY: Medikit last year outbid several other Japanese healthcare companies to sign an exclusive distribution agreement with an American company, Cardio Vascular Systems [CSII], to sell a product called Diamondback 360 in Japan. It’s used in a pre-treatment procedure on severely calcified arteries to increase the effectiveness of stent or balloon catheters. Based on estimates of the number of patients in Japan suffering from calcified coronary and peripheral arteries, we think this product could ultimately generate several billion yen in revenue for Medikit, not insignificant for a company with current annual revenue of ¥16.6 billion. Commercialization of the product is scheduled to start next year.

Are you satisfied with the capital allocation here?

JY: We were happy to see the reinvestment in the business with the CSII deal, and the company over the past two years has been increasing dividends and has bought back 10% of the shares outstanding at only 2x EBIT. But cash on the balance sheet still represents roughly half of the current market cap and we think there’s plenty of room for more capital return. The company celebrates its 45th anniversary next year, so we’ve suggested they take the opportunity then to announce a long-term business plan that includes a clearer strategy on the use of cash.

How are you valuing the shares at today’s price of around ¥4,650?

JY: Acquisition multiples in medical devices tend to be fairly high, even in Japan, with acquirers typically paying 15-20x EV/EBIT. To be conservative, we apply a 10x multiple to our roughly ¥4 billion 2018 EBIT estimate and add ¥22 billion in net cash and investments to arrive at a fairvalue estimate of ¥6,500 per share. Given the cash level and the stability and profitability of the business, we think we’re also very well protected on the downside.

Describe the potential you still see in EM Systems.

JY: We first invested in EM Systems eight years ago after the company changed its business model from selling its software for a large upfront payment to a more attractive one with lower upfront fees but also monthly maintenance fees and a fee per processed prescription. It’s an excellent recurring business – there are 700 million prescriptions processed in Japan every year, about six per person, and this number is increasing as the population ages.

The main competitors, Panasonic Healthcare and a small division of Mitsubishi, have 10-20% of the market and both appear more focused on other areas than the dispensing pharmacies in which EM is so strong. The remaining competitors are much smaller and struggle to keep up with rising regulatory costs. That allowed EM to buy three smaller and barely profitable competitors in the past few years for cheap prices. We expect it to continue growing its market share for the foreseeable future.

The company also has a number of promising growth initiatives underway. It recently began selling software systems for small medical clinics and for nursing care. It’s in a partnership with Medipal [7459:JP], one of the largest drug distributors in Japan, which has integrated EM’s software into a new service called PRESUS (for Pharmacy Real-time Support System), which helps client pharmacies streamline their order, inventory and delivery functions. We also think the company has the potential to better monetize all the pharmacy prescription data it collects, which could be very valuable both to drug companies and healthcare regulators.

Your take on management?

JY: Kozo Kunimitsu, now the Chairman, founded the company and was CEO when it changed the business model to more recurring revenues. This initially caused a large decline in reported sales and led to three years of losses before things started to improve. We like management that can take short-term pain for long-term gain. We have a good relationship with company leadership and they will often call us when they want investors’ input.

The stock is up 50% in the past year. What upside do you still see from today’s ¥1,820 price?

JY: Based on prices at which relevant deals have been done and the fact that this is a high-quality operating business with good growth prospects and margins, we think it should be valued at 10x our 2018 EBIT estimate of ¥2.5 billion. On top of that the company has roughly ¥4 billion in net cash and also owns a large office building in front of Shin-Osaka station, which at a 5.5% cap rate we value at around ¥14 billion, after the potential tax burden. Altogether, our intrinsic-value estimate for the shares is close to ¥2,500.

It really doesn’t make sense for a software company to own such a large building – they occupy two of the floors and lease out the other 13 – which accounts for 75% of the company’s fixed assets. We have suggested they consider either selling the building outright or putting some debt on it, using the proceeds to buy back shares at less than intrinsic value. We’ll see what happens.

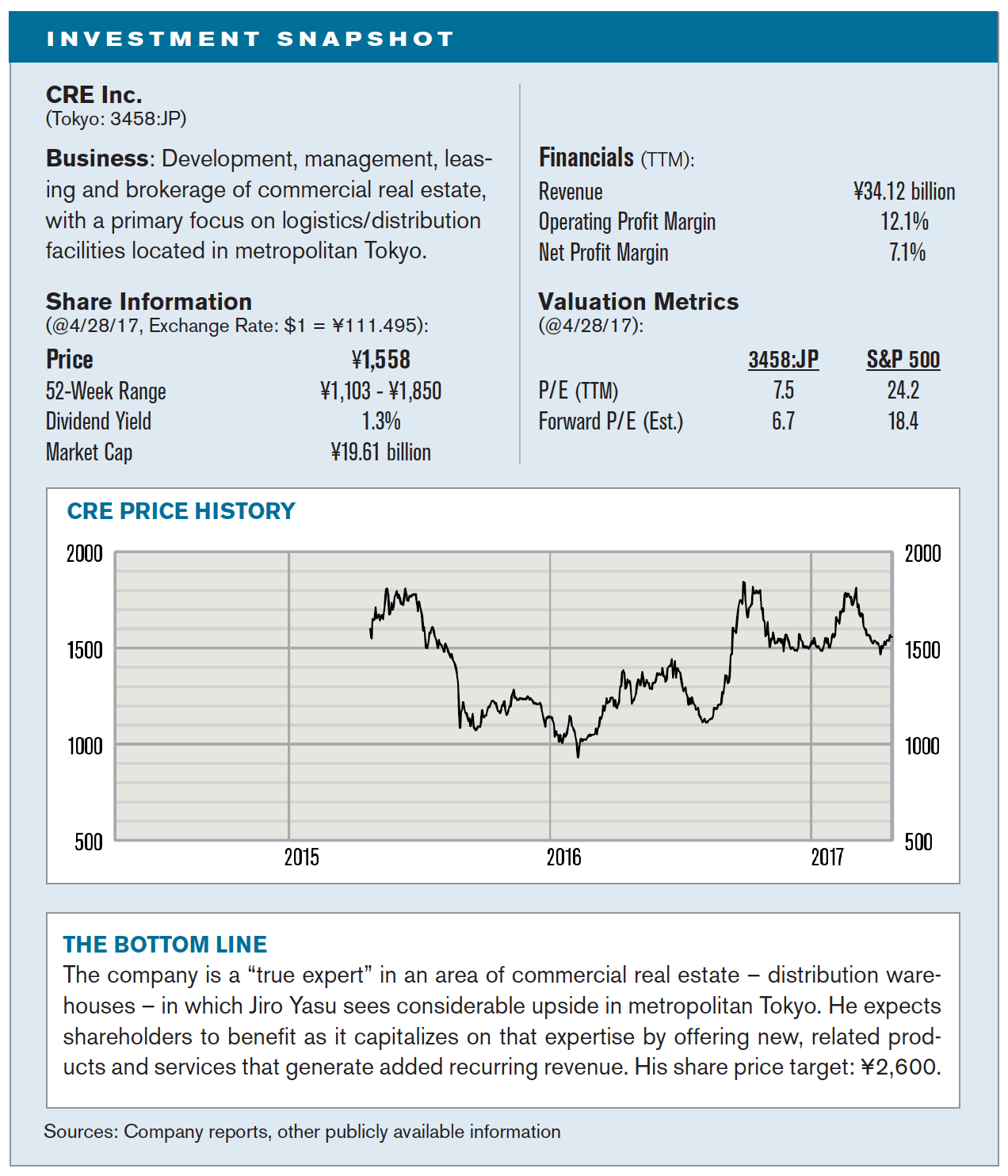

From software to real-estate development, what attracted you to CRE Inc.?

JY: We invested in CRE in 2015 when its stock declined after its initial public offering and we are now the third-largest shareholder. The company primarily develops and manages distribution warehouses located around metropolitan Tokyo. It usually develops three to four warehouses per year and sells them off to REIT’s or other investors while maintaining the contract to manage them.

They are true experts in this area of the market, which we consider quite attractive. Many existing warehouses around Tokyo are old and small and there’s great need for more cutting-edge, large warehouses that can save customers money and better handle ever increasing volumes driven by the growth in e-commerce.

Revenues for the development business can be lumpy depending on the number of warehouses developed and sold each year, so we don’t ascribe a high valuation multiple to it. On the other hand, we like the property-management side of the business because it is based on long-term contracts and is quite stable.

Describe your relationship with CRE’s management.

JY: We know the controlling family well and in August of last year signed an agreement with them to assist in creating a long-term business vision for the company and a new capital-allocation plan. Our main input has been to focus on expanding recurring revenue streams from master leasing, property management and REIT management. We also suggested the company implement a capital-allocation policy that calls for at least 50% of the cash flows generated by recurring-revenue business lines be paid out as dividends, and for cash flows from the development business to be used opportunistically for buybacks, dividends, M&A and new developments. They have adopted most of our recommendations.

As an example of developing new recurring-revenue streams, the controlling family launched a REIT, with assets of about $400 million, which buys warehouses developed by CRE. The company manages this REIT so it earns management fees for that as well as fees for leasing and managing the warehouses. CRE has also developed a master-lease business in which it earns fees for acting as an intermediary between owners of warehouses and the occupants.

How cheap do you consider CRE’s stock at today’s ¥1,560 per share?

JY: At the current share price the market cap is over ¥19 billion and the enterprise value is over ¥24 billion. On our 2018 estimates, we value the development business at 5x EBIT and the recurring-revenue businesses at 8x EBIT. Add to that net cash on the balance sheet and we arrive at a price target of around ¥2,600 per share, almost 70% above today’s price.

Turning to Japan as a whole, there’s much debate about the financial reforms pursued by Prime Minister Abe since he came into power at the end of 2012. Are you a fan, a critic, or both?

JY: With respect to corporate governance, I do think there has been a significant improvement in the last three or four years in Japan. The government is mired in debt, so the administration set its sights on trying to get some of the $2 trillion of cash sitting on Japanese corporate balance sheets moving around the economy to foster growth. If more cash was returned to shareholders, ROEs would improve, equity multiples would expand, and that would have a further positive wealth effect on the economy.

To put pressure on companies to do something with their cash stockpiles, the government has implemented a series of policies such as new corporate-governance codes that push for more outside directors, Government Pension Investment Fund reforms, and the launch of the JPX-Nikkei 400 index, which consists of 400 large-cap companies that are selected primarily based on having high returns on equity. The government pension fund now uses that index as a benchmark and it has become sort of a new elite club which Japanese companies – which often play follow the leader – want to join.

Five years ago when we’d talk with CEOs about return on equity or buybacks or capital allocation, many didn’t try to understand. Today at least they understand these are important issues. You see more companies announcing they will return more than 100% of annual cash flow to investors, and share buybacks overall have significantly increased. It’s all coming off a low base, but we believe the trend is positive and will continue to improve.

All that said, in picking stocks I try not to have a very strong opinion on the macroeconomy. I’m not counting on strong improvement in the general economy or in how stocks are valued. I assume life is tough and will remain tough. In that environment I’m looking for companies that can still make good money.