Technical analysis

When I started my career at Daiwa Securities America’s US equity department in 1996, my first client was a portfolio manager of a mid-sized Japanese insurance company. He was a believer in technical analysis. My sales calls with him were quite odd along the following line:

Me: Good morning, Mr. Sato (not true name, of course), I think regional banks like Bank of Boston (Ticker: BKB) are attractive investments because deregulation will drive consolidation. BKB may be acquired at a large premium.

Mr. Sato: That sounds interesting. Let me see the chart of BKB. Hmm…. I think the A wave is over and the B wave just started. Don’t you think, Yasu-san?

Me: (I have no idea what these waves mean) Yes, yes, I think so, too. Definitely B. So, that means we should….

Mr. Sato: BUY. Definitely buy. Buy me 5,000 shares of BKB at market, Yasu-san.

Me: Yes, sir. Buy 5,000 shares of BKB at market. Let me call you right back.

Mr. Sato sold BKB a few months later at modest profit when the B wave completed. BKB was eventually acquired by Fleet Bank in 1999. He played around with shares of regional banks after this successful trade. As he enjoyed making trades based on my tips and his technical analysis, we got very close. He kindly introduced me to some famous macro traders who made bets based on technical analysis. They told me that all famous macro money managers such as Paul Tudor Jones or Louis Bacon made billions using technical analysis.

I read a few books about technical analysis and drew some lines on charts. However, it never made sense to me. Therefore, I thought I could never have a career as a money manager because I didn’t have the ability to forecast the future by using mysterious technical analysis. I thought only a few geniuses could become successful money managers and I was not good enough.

Over the years I kept in touch with Mr. Sato and we had dinner together right before his retirement from the insurance company a few years ago. I don’t know exactly what happened, but it seems his portfolio management career did not last long and his last job with the company was as the head of the internal audit department. He was still a strong believer in technical analysis. He said he was able to forecast most major market movements of the past few decades such as the dot-com bubble and crash, the GFC, etc., well in advance. I congratulated him because he must have made so much money over the years by making correct market calls. However, he said he actually made no money. He said making money for himself using such powerful technical analysis is a sort of blasphemy of the holy charting[1]. I did not know what to say, but I congratulated him on a happy retirement anyway….

Trading tech stocks

Although I gave up on a career as a portfolio manager, I was trading stocks in my personal account. It was the late 90’s and US equity markets were booming. I felt that making money seemed easy. I just needed to watch CNBC and buy some popular tech stocks that kept going higher and higher. In 1998, I left Daiwa and joined First Eagle (f/k/a Arnhold and S. Bleichroeder) where I was promoting the firm’s risk arbitrage fund to Japanese investors. My personal trading style had not changed much and I was still betting on tech stocks. I even put my 401K money into the tech-heavy Janus funds. I did not pay much attention to value investing then since it seemed to not be working and many investors were saying it was dead. I didn’t know where Omaha is then.

After finishing a spectacular 1999, a few things around me changed. First, I got engaged to my wife. We started going out when we were just 17 years old. 10 years later (including 4 years of me living in NY and her living in Tokyo), we decided to get married. I wanted to buy a nice engagement ring for her and needed to plan how to pay for our wedding. February was usually bonus time at First Eagle. I think I got a decent bonus that year, but I was also granted an opportunity to buy shares of the firm. Therefore, most of my bonus was needed to go to the firm’s shares and taxes, and not for a ring or wedding. It led me to look into my little tech portfolio, which was sitting on nice unrealized gains.

My colleague and good friend Joe Keenan (I called him Joey) sat across from me at First Eagle. Right after we got our bonuses, I saw him talking on the phone about tech stocks. He was trying to get tips from friends and relatives, apparently having missed the rally in 1999. Now, he was ready to invest his entire bonus into tech stocks. I also gave him an idea, Tivo, which I claimed was the Yahoo of video. It was a $3 billion market cap company with $40 million of sales. Its PSR (price to sales ratio) was “just” 75 times. Many tech stocks were above 100 PSR then, so it was cheaper. Joey decided to include it in his portfolio. As I am writing this blog, I learned the company was acquired at a valuation of $1.8 billion in June 2020. I am sure he dumped the stock at some point. But if he owned it till the end, his total return was -86% according to Bloomberg (Sorry Joey.)

Watching Joey and other colleagues jumping on dot-com speculation reminded me of the late 80’s in Japan. Both my grandfathers passed away around the peak of the Japan’s bubble economy. I remembered that my father was quite popular at their funerals. Many relatives tried to get stock tips from him since he was the president of my family’s brokerage firm. Also, back then, the Japanese media was busy reporting get-rich-quick stories like an office lady who bought some shares in NTT at the IPO and made a killing. Such stories gave regular people FOMO and pushed them to make speculative bets. By the way, shares of NTT are still trading below the IPO price of 30 years ago (although including dividends they have exceeded that level.)

So, I thought US tech stocks were definitely in a bubble and would eventually crash. Instead of selling a few stocks in my portfolio, I decided to sell EVERYTHING. My biggest investment back then was Motorola. I owned shares of the cable set-top box manufacturer General Instruments, which was acquired by Motorola through a share exchange. Motorola was trading around $200 when I sold out. It finished 2000 around $80. I told my wife that if our engagement had been delayed by a few months, her diamond would have been much smaller.

Ready to learn value investing

Another big event for me at that time was the famous global value investment team led by Jean-Marie Eveillard joined our firm. Jean-Marie famously said that he’d rather lose 50% of his clients than lose 50% of his clients’ money by investing in things he didn’t understand like tech stocks. He avoided TMT stocks and kept his value discipline during the dot-com bubble. As a result, he underperformed against major indexes for several years. He was a bit too optimistic about clients’ loyalty since he actually lost 70% of clients and his AUM declined from $6 billion to $2 billion. Also, the parent company of his funds decided to sell the operation (he said an executive of the parent calculated the days to reach zero AUM by extrapolating the redemption trend.) They had a tough time finding a buyer, but First Eagle picked it up in the end. I remember some people at First Eagle were somewhat skeptical about the validity of value investing. Nevertheless, the value team became my co-workers at the beginning of 2000.

Jean-Marie was not alone in suffering during the dot-com bubble. Barron’s published a cover article titled “What’s wrong, Warren?” in the December 27, 1999 issue[2]. In his annual letter, Buffett said 1999 was his worst absolute and relative performance and his capital allocation grade was D. During 1999, Class A shares of Berkshire Hathaway declined by 20% while the S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite appreciated by 20% and 85% respectively. Some others value investors shut down their funds. Julian Robertson’s Tiger Management announced plans to close at the end of March 2000[3], ironically the month the Nasdaq peaked. In addition, some famous value portfolio managers who maintained their value discipline during this period lost their jobs, such as Robert Sanborn of Oakmark Fund and Tony Dye of Phillips & Drew.

Back to my story at the office. After selling out all my tech stocks, I instantly became a tech bear (I guess you can call this confirmation bias). As tech peaked in March 2000 and started free-falling, I felt GOOD (sorry again Joey). We started seeing some money managers saying they knew this was coming. Value investors were the most vocal. That led me to learn about value investing from my new colleagues.

Jean-Marie recommended a comprehensive reading list including some books, Louis Lowenstein reports, Buffett’s speeches and shareholder letters, etc. He kindly went over some examples of his positions like Bank of International Settlements, Buderus, Shimano, and some champagne and cognac companies. Unlike my experience of technical analysis, value investing instantly made sense to me. The most important thing about value investing is having a margin of safety by investing at a price with a large discount to intrinsic value. The Chinese character of my last name (“安” Yasu) has two meanings: safety and discount. I thought I have the perfect last name to be a value investor. In my early days of trying to learn technical analysis, I thought that being a portfolio manager was not for me after all because I couldn’t forecast the future like some market genius. However, while Jean-Marie seemed like a very smart person, I didn’t feel he was super-human. In fact, he looks more like a regular French guy (sorry Jean-Marie). So, I thought that if I pursued value investing, there might be a chance for me to become a portfolio manager like him one day.

Value vs. Growth

5 Year Annualized Total Return

11/30/2015 – 11/30/2020

| Growth | Value | Difference | |

| S&P500 | 17.64% | 9.37% | 8.27% |

| MSCI World | 15.94% | 6.84% | 9.10% |

| MSCI EAFE | 9.73% | 3.63% | 6.10% |

| Topix | 6.87% | -1.81% | 8.68% |

2020

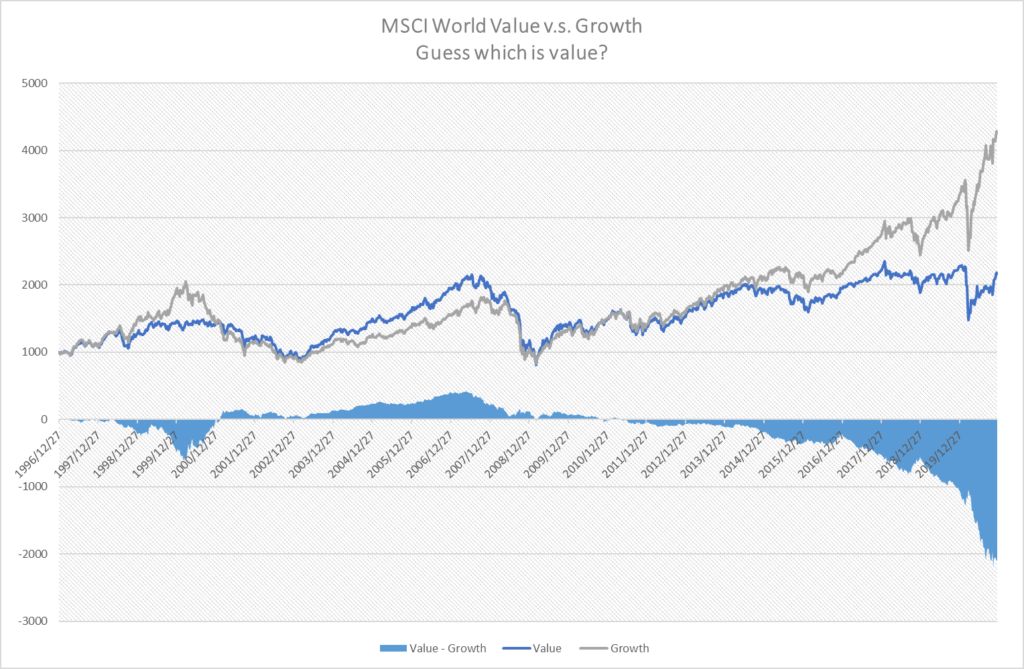

Fast forwarding 20 years, today value investing is in trouble again. It has been underperforming against major indexes for years, which drove capital to away from active value funds and into passive funds. The Covid-19 pandemic made the situation much worse. Not only tech giants, but also stay-at-home tech beneficiaries like Peloton, Netflix, Zoom, or Slack became hot stocks, while value-y industrial, financial or energy stocks are now disliked.

The table above is the 5-year annualized total return of various growth and value indexes. As you can see, growth indexes have outperformed significantly over the past 5 years. The absolute return of the Topix subindexes is uniquely bad. Topix Growth is even worse than the S&P 500 Value.

We have once again started seeing articles saying value investing is dead or that some value shops decided to shut down, just like in the late 90’s. Back then, the dot-com bubble eventually burst and managers and investors who stuck with their value discipline were well rewarded. Of course, nobody knows whether value investing will recover this time as it did before.

Jean-Marie always said that value investing works “over time”. Not every single year. If you decide to pursue value investing for your career, that means you accept that you will underperform and suffer from time to time. That is why you need to have the appropriate temperament for it. But, even with the right mindset, as underperformance continues for several years, Jean-Marie said “there were days when I thought I was an idiot.[4]” Even he suffered self-doubt. So, it is not easy.

Some money managers or sell-side strategists have been predicting that value stocks will recover soon because the valuation gap between growth stocks and value stocks widened to levels we have never seen before. This sounds odd to us because we believe the future is uncertain. Also, as Keynes said, “markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.” Calling the right timing of mean-reversion sounds more like technical analysis to me.

So, what do we do now?

The investment styles of great value investors evolved over their careers within a large value tent. Buffett evolved from Ben Graham-like cigar-butt investments to high-quality growing businesses that he never sold due to the influence of Charlie Munger. Buffett did not invest in tech during the dot-com bubble days. But, he made a big investment in IBM in 2011. It did not turn out to be a successful investment and he exited at a modest loss 7 years later. However, the mistake led him to a much larger and more successful investment in Apple. Today, he owns shares of Amazon as well. He also evolved from a US-only investor to a more global investor. He has owned shares of BYD for over 10 years and became a large shareholder of Japanese trading houses this year.

Similarly, Jean-Marie also started out investing in statistically cheap companies. It was because he was running a small fund by himself and did not have the resources to do much qualitative work. He ran the fund by himself for 7-8 years. As his fund grew in assets and he could afford to hire a few analysts, he expanded into more Buffett-like franchises by doing more qualitative work. His team also became investors in “mature” technology companies like Microsoft, Intel, and Cisco 10 years after the bubble burst.

Li Lu, a Chinese-American investor who is also a friend and an adviser to Charlie Munger, took a similar path. He once said in an interview[5] that everybody has to start from dirt cheap companies because we are not experienced enough and we don’t want to lose money. He said over time he also fell in love with strong businesses. He also evolved from a US equity investor to a China and Asia-focused investor. He even became a successful venture capitalist, which is quite rare in the value community.

At Varecs, we also have been moving around to find our own comfort zone within the value tent. We, too, started out investing in super cheap companies. But, since Japanese companies were all dirt cheap when we started, some of them happened be better businesses. As time went on, we started noticing differences in the business performance among our holdings. As we paid more attention to business quality, we were able to build conviction in a few companies and size up our investments with them. On the other hand, there were some companies which we thought were no brainers due to their valuations (like negative EV), but which turned out to be quite the opposite. Their businesses did not grow and management teams did not change their capital allocation. So, eventually we gave up and exited them at modest profits.

Our engagement played an important role when we decided to focus on better quality companies over the years. Initially, we spent more time with no-brainer opportunities. We thought the only thing we needed to do was change how the management teams allocate capital. They traded at negative EV, meaning they had more cash than market capitalization. So, we can get back all our invested capital back when/if the company paid out excess cash to shareholders. So, we thought there was no downside. We thought the company should have some value even after paying out the cash since the business still produces profits. We thought that would be our upside. Basically, we asked them to pay out OUR cash because it was the right thing to do. However, they said they would not do it because it is THEIR cash and they needed it for rainy days. Our discussions hit a dead end. Also, we learned a lot about the quality of businesses and management teams through such discussions. Basically, they were pessimistic because their businesses had lots of issues. But, since the management did not own many shares and they were old and about to retire, they didn’t have much incentive to make big changes. So, that was why we gave up.

While we were getting tired of meetings with unmotivated management teams of undervalued companies, discussions with a few other companies were quite refreshing. For example, a CEO of $50 million software company laid out his long-term strategy to be a half billion dollar-company in 10 years. Another example was a founder of a medical device company who told us that his long-term plan was to be a true global company when his overseas sales at the time were just 5% of revenues. As we had follow-up meetings with such companies, we tended to be more impressed by the quality of their businesses. And these management teams have been quick learners from our suggestions and made decisive actions. Such mutual respect and constructive relationships allow us to commit larger amounts of capital with them.

These days, Japanese markets have become a bit more challenging and we can no longer find high quality businesses trading at negative EVs. There are still negative EV or super-low PBR companies in Japan, but we tend to think they deserve such valuations due to problems with the business and/or capital allocation. So, we, too, focus on better quality businesses even though we have to pay higher multiples. We tend to build conviction over time through constructive engagement with the management team.

Columbia University professor Tano Santos hosts the “Value Investing with Legends” podcast, which has been one of my favorites. He starts it by saying, “Value investing is more than an investment strategy. It is a fundamental way of thinking about finance.” If it were just a way to make a quick buck, it would have never attracted so many talented people. Since value investing is loosely defined, it forces practitioners to find their own style. And it seems that many successful investors evolved by learning from their own mistakes and eventually found their own niche.

One of the important pillars of value investing is humility, which Jean-Marie said is necessary because the future is uncertain. Humility forces us to make conservative assumptions when we think about the true value of a business. It also leads us to seek a large discount to intrinsic value when we invest. What’s more, it forces us to have some diversification within the portfolio. Some investors, like Mr. Buffett, prefer a concentrated portfolio. But, even he never bets everything on one company. Also, common sense plays an important role in this process and keeps us away from things we don’t understand.

Concluding Thoughts

Some value investors have been blaming things like low-interest rate, central banks, indexing, FAANG mania, Robinhooders, private equity, etc. for their underperformance. But the world has changed so much, and there is no guarantee the things that worked in the past will work in the future. Price is what you pay and value is what you get. That will never change. But, the value of businesses changes as the world changes. So, we need to change as well.

Not long ago (7 years ago to be exact), ExxonMobil was competing with Apple to be the world’s largest company by market capitalization. Since then, Exxon has lost more than half its value, while Apple’s has more than quadrupled. Similar changes occurred in Japan. At the peak of the Japanese bubble, over half of the 10 largest Japanese companies by market capitalization were banks. They were all later consolidated into 3 megabanks and none of those are among the top 10 now. The largest, Mitsubishi UFJ, which was formed by the mergers of Mitsubishi, Tokyo, Sanwa, and Tokai, is ranked 18th. A global comparison may be more interesting. Japan occupied more than 40% of the MSCI World Index at the end of 1989. Today, it is less than 8%. The entire market is worth less than the GAFAM stocks. We don’t know how these positions will change over the next 10 years. But, we are almost sure it will change a lot and we need to be open minded about new investment opportunities due to such leadership changes.

From my earliest days in this business, my personal investment philosophy has undergone quite a lot of change – from the early (and thankfully brief) days exploring technical analysis, to owning high-flying tech stocks, to my fortunate discovery of value investing. Even after finding an intellectual “home” in value investing, we continue to adapt and explore new ways to apply value principles. As long as we are humble and disciplined about what we pay, we believe mistakes won’t kill us. Value investment is not a magic formula to pick stocks. Instead, it is more like a framework which allows us to try new things, make mistakes (but survive), and eventually evolve. That is why we still are proud to be value investors.

[1] A few years later, I found a quite similar story about technical analysis in the book “Where are the Customers’ Yachts” by Fred Schwed. This book is highly recommended by Warren Buffett

[2] https://www.barrons.com/articles/SB945992010127068546

[3] https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB954452457785094719

[4] https://www.barrons.com/articles/profiling-wall-streets-bright-lights-1432956817https://www.barrons.com/articles/profiling-wall-streets-bright-lights-1432956817https://www.barrons.com/articles/profiling-wall-streets-bright-lights-1432956817

[5][5] https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/valueinvesting/sites/valueinvesting/files/files/Graham%20%26%20Doddsville%20-%20Issue%2018%20-%20Spring%202013_0.pdf